The Lore of the Black Coats Road

Imminent High Court Shift Calls for the End of an Age

In the daily rush of life, things we encounter every day often settle comfortably into the backdrop. They do not register as remarkable unless they are threatened with eviction from the thread of the familiar. The High Court road, forming the posterior artery running behind the impressive eminence of Qaiser Bagh and its regal, quite splendor, formed one such crucial backdrop trail for me, growing up in Aminabad. Any trip around the city entailed passing at least one of its famed landmarks and standing at the crucial intersection leading on the left to Chakbast road, turning towards the British Residency and on the right to the Baradari, through the inviting Nawabi Western Gate, it took a certain deliberate decision to choose to tread on straight to the land splattered with black robes, passing the High Court.

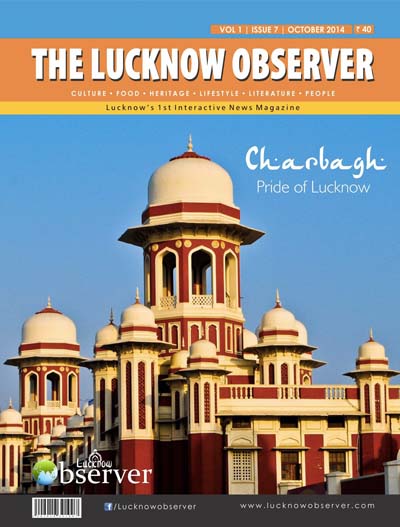

The red yellow Indo-Sarcenic style building of the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad High Court set in high security on the road known by its name, Kutcheri road has formed an appeasing landmark of the city, resting in the centre of the city among many other of its beautiful ‘memorabilia-c’ monuments. It would complete one fifty years of its proud and hefty, hustled existence this year; its celebrated centenary was observed in 1966.

The reason that its location is so important is why it is being uprooted to a new facility on Rae Bareli road, with a better, more suitable infrastructure that allows maximum attendance and efficiency for the legal proceedings. The convenience and attraction of new premises is welcome, but it brings an age long institution to a sad close. The building will be handed over to the archaeology department.

Where the road starts, with first the revenue department and the bar association on the right it opens up like a chapter in a book with curious characters strewn all across it. The parrot fortuneteller, predicting the day’s turnout in the court, success or failure? The counterfeit gems seller, ensuring the former; the local (hugely misplaced) dentist with his primitive scary tools, and the occasional sane person who makes use of his service, all sit there on the roadside to enchant you into their out of time, determined business pitch. The photographer guaranteeing in bold letters a one minute delivery rate, hidden under the faded cloth of an old view camera- time takes a little back flip as you stop here.

Lawyers in black robes preside all over the area, marking it with their swift, directed strolls, languid or pointed discussions, constant groups of deliberation at tea stalls, the chasing around of typists and getting the documents prepared; lunch hour crowd, when the entire court house it seems dissolves on the passage over food and in-house events.

An excerpt from Vikram Seth’s ‘A Suitable Boy’ reads, “There were a few grey clouds in the eastern sky, but not rain-bearing. The road to Residency past the fine-red brick building of the Lucknow Chief Court-now the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad High Court-was uncrowned.” Well, Lucknowites know only too well that can only happen in a book or a Sunday!

On Mondays and at all important work hours, there is a rush of traffic and terrible congestion due to vehicles clogging to and from the court, causing disruption at what is otherwise a somewhat quite juncture for traffic, one significant cause that called for the new arrangement. But many say that it is not going to make any difference, as the new building itself is located on a highway and stakeholders predict massively disruptive traffic jams. “Instead of locating it on an off road position, outside the city, situating it on a highway is not going to help the old traffic problem and it is only going to cause more problems only, for the people to navigate, move around and avail facilities which were so readily available here where all the lawyers were used to and aware of the convenient services”, says Mr. Hemant, who owns a copiers shop, right outside the court, one of many small business flanking its front walls which stand to be displaced and disadvantaged by this change.

“We have not been assigned any place, we do not know anything of what we may be entailed of or not in the new building, but given the location, the rentals must be very high, and they won’t allow any gains from the business, plus the cost of transit, it is a total loss for us.”, he laments.

Typewriters, photographers working in the urgency of a one minute timeframe abound here and stand to lose a lifetime or at least half of a habit and easy trade in their claimed and won domain. Sitting under makeshift sheds that have been their chosen workplace for years, the work that they have braved through rains and heat, and the clientele and familiarity they have forged, all are being moved to uncertainty.

Ravindra Gaur who has worked as a typewriter here for over fifteen years says, “Most of us will move to the new building. It will be very inconvenient but there is no other option. This is the only work I know and I need the same kind of business to continue with. Here or anywhere else I can’t hope to find it in such amount. It has become a way of life, the familiar faces. The same lawyers keep coming back to us; they trust us and we depend on them. Everyone has his chosen typewrite or copier whom they bring their work to, and we look forward to serve them. That cannot be allowed to change, as far as it is possible, I doubt if it is at all, but we do plan to shift too.”

Ehsan Hussein who owns a shop here adds, “We have made acquaintances, twenty years I have spent here. It is not possible for me to shift. And with time it won’t be possible to continue with those people you have known so long.”

The entire bar council with its stream of notary clerks at the ready will be shadowed by this move.

Inside the court, the giant Indian judiciary, the important proceedings and people, they also lose a known way, a mastered place and for many the place they started their career in law at.

Mr. Rajesh Pandey looks at it more rationally “The shift is going to divide the work and limit it too. Here a lawyer could work for both the lower courts and high court but that would not be possible there. If someone’s assigned work here, they would have to rush to the lower court. Only those who have an established practice could succeed there, the new comers or the lesser experienced would be at a grave disadvantage.”

The reasons conjured up are many and relevant too but the truth of the matter is, it is the end of a glorious period.

The highest Court in Awadh comprising 12 districts was established in 1856 with a Judicial Commissioner presiding over it. It was made into the Chief Court at Oudh in 1925. It held jurisdiction over the 12 districts of Awadh. The original jurisdiction however was curtailed in 1937 by the Government of India (Adaptation of Indian Laws) order, 1937.

Mr. K. Banerjee, senior lawyer of the high court recalls, “When I started out here it was a different atmosphere all together. There used to be discipline and dignity in all proceedings. The entire premises would be quite to maintain the sanctity and silence in the trials. People behaved formally and cordially in the workplace, with colleagues or seniors but there were a general good will and not the cutthroat competition of today. Neither were the halls so stuffed with robes. The modern day rhetoric is also starkly different. Many eminent lawyers would come here from across the country to defend some rich party. It was a privilege to work with great minds, honest lawyers. And being a lawyer in those days meant you were sharp, witty, skilled and very knowledgeable. That cannot be said of today’s lawyers I am afraid”

Another recalls, “The corridors in front of the court-rooms were matted so to prevent the sound of footsteps from disrupting proceedings. The Bar Association had two rooms only. The seniors occupied the first room; the second was the library. The juniors had to sit either in the library where they could not even whisper or they had to take refuge in the court-rooms bearing the brunt of the good and bad lawyers arguing their cases.”

It was also a matter of the kind of cases being fought. The clients at the beginning were only landlords or farmers, pitted against each other.

Mr. H. K. Ghose, President, Avadh Bar Association, Lucknow has written in ‘Reminiscences of over half a century of the Oudh Courts and Bar’, a commemorative volume published in 1966, “In 1915, when I settled down in Lucknow, the civil litigation in the Court of Judicial Commissioner of Awadh (the highest court of appeal) and in the Courts subordinate there to mainly consisted of cases under the Oudh Estates Act (Taluqa cases) involving intricate questions of law of inheritance and custom as well as cases of preemption, Hindu law of inheritance, adoption and wills, mortgages and transfers by fathers and widows, challenged by sons and heirs and a few cases of family settlement.”

All of this succeeded by the broader concept of judiciary with freedom and the constitution in place. But the charm of the profession, the case riddled conversations in groups over tea and the unique call of the present high court premises, asserting its own place in the scheme of things, will some become things of fond remembrance and some will continue to be.

Nikita Gupta

(Published in The Lucknow Observer, Volume 2 Issue 23, February 2016)