Rashid Jahan

Writer par excellence…

At 16, Rashid Jahan left the sheltered world of Aligarh and the safe confines of the girl’s school to study at the Isabella Thoburn (IT) College in Lucknow. Here, new intellectual vistas began to open up. Though a science student, she read Dickens, Keats, Shelley and Thomas Hardy as also Tolstoy, Pushkin and the Russian masters as well as Maupassant and Balzac. While still in college, she wrote her very first story called ‘When the Tom Tom Beats’ in English; it was translated by Ale Ahmad Suroor, who would later become a close friend, into Urdu under the title ‘Salma’ and became quite popular.

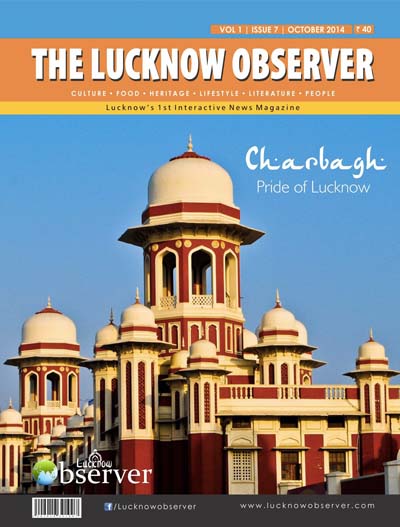

These two years between Aligarh and Delhi were carefree years filled with books, sports and the many extra-curricular activities that the teachers at IT College encouraged. While still at an all-girls school like the one she had left behind at Aligarh, IT College was, in many ways, an altogether different world. For one thing, the emphasis on English was new to someone like Rashida who, though knowing English, nevertheless came from an Urdu-speaking milieu. For another, the exposure to girls from different backgrounds was far greater and the emphasis on purdah was negligible. Though housed in secluded quarters in the fabled Char Bagh campus, the girls were by no means cloistered. Inside the college, they swam, played tennis, badminton and basketball, debated, acted in plays, recited poetry, and were introduced to the latest cultural and literary trends. Outside the College, they were permitted to go to the movies and indulge in ‘Ganjing”, a form of recreation unique to Lucknow comprising as it did a leisurely stroll along the fabled colonnaded market of Hazrat Ganj.

Set up primarily for native Christian girls, IT (as it was generally known) drew girls from all the ‘good’ families – Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, and Parsis mingled freely with the Christian girls. However, unlike the Christian girls – the majority of whom were on freeships or whose education was subsidized either by the Church or well-meaning members of the domiciled community – the non-Christian students paid full fees and were, naturally, from privileged if not aristocratic families. Liberal Indian parents of a certain class displayed more similarities than differences; their daughters, thus, tended to form a sorority of sorts making close friendships across distinctions of religion, caste or culture.

The benefits of a liberal English-style education mingled harmoniously – in the case of Rashid Jahan and successive women writers such as Attia Hosain (1913-1998) and Qurratulain Hyder (1928-2007) who followed her at IT and came from similarly privileged backgrounds – with a family background steeped in the values of sharif culture. We can get a glimpse of the charmed world that the young ladies occupied in Charbagh in the writings of both Qurratulain Hyder and Attia Hosain and can well imagine Rashid Jahan here from 1921-1923. Ismat Chughtai who followed her beloved Rashida Aapa from the school at Aligarh in 1933, has written colourful accounts of IT as well as drawn on several characters that she met during her days at the College in novels such as Terhi Lakir (The Crooked Line); she has also devoted a whole chapter to describing life among its porticoed halls, libraries and sports fields in her autobiography. Ismat describes how she could move about freely both inside the college and outside, go out to the bazars, meet people, even boys! She writes how the rule of freedom within reasonable limits implemented by her fair-minded American teachers went a long way towards making her what she was. Her views on the enforced purdah and seclusion practiced in most Muslim homes appear in different ways in much of her writing: ‘The fear of the other sex that is planted in a girls’ mind in her childhood has very deep and complex ramifications.’

Rashida had discarded the purdah by the time she had gone to Lucknow; her mother, Ala Bi, had agreed that she would be singled out and her education might suffer. Free from its restrictive anonymity, Rashida blossomed. Always a bold and fearless girl, she had been a natural leader since her childhood days. Given her family background and the array of distinguished visitors who routinely visited Abdullah Lodge, she was attuned to the great national discourses of her time: the Swadeshi, Home Rule, Civil Disobedience, Khilafat Movements were discussed in her parents’ home by those most intimately connected with these great socio-political stirrings that were quickening the national consciousness. Her eclectic reading – thanks to open-minded teachers at Aligarh and Lucknow as well as the liberal humanism practiced by her parents – had opened her mind to the intellectual debates of the 1920s. Early exposure to nationalist leaders such as Maulana Mohamed and Shaukat Ali, their mother Bi Amman as well as Maulana Azad, members of the Fyzee and Tyabji clan introduced her to new ideas and new ways of seeing the world. While by no means dogmatic, the American missionaries who ran IT College were, essentially, preparing their pupils to live and cope in a colonized, deeply polarized world. Rashida could, from her early teens, see the cordon sanitaire that segregated the two worlds: the privileged/under- privileged, educated /uneducated, rich/poor, colonizer /colonized.

During holidays, she would return to Abdullah Lodge at Aligarh. But in Papa Miyan and Ala Bi’s home, holidays were not meant to be an extended period of leisure; Rashida was expected to pitch in and lend a hand at whatever work needed to be done. It could be taking classes one day or informally teaching the servants and their children to read and write on other days. Since Ala Bi had taught all her girls immaculate sewing and dress-making, Rashida would knit and sew, often make clothes for the extended family of helpers at the school and stitch woolen clothes for the winter. These chores would be interspersed with fun-filled family outings; Ala Bi would plan picnics to the waterworks at Narora or to a pond to pick water chestnuts and Papa Miyan would gather his flock for recitations from the choicest Urdu poets, or King Lear!

After completing her Inter-Science from Lucknow, Rashid Jahan moved to Delhi to study medicine at the Lady Hardinge Medical College in 1924…. Rashid Jahan joined the Provincial Medical Service of the United Provinces after graduating from the Lady Hardinge College in 1929 and after, a first stint as a Medical Officer in Bulandshahar, was posted to Lucknow in 1931. This second stay in Lucknow, longer than the first, would prove to be a turning point in her life and set her on a trajectory that would transform her from Dr Rashid Jahan to Comrade Rashid Jahan and thence to Rashid Jahan ‘Angareywali’.

Dr. Rakhshanda Jalil