Friends from the Other Side

Hardships Faced in Unison

The partition of India in 1947 was, perhaps, the most excruciating pain that Mother India endured when her children senselessly massacred one another in the name of religion. According to the United Nations, approximately fourteen million Indians were displaced – the largest mass migration in human history and an estimated 3,00,000 to 5,00,000 innocent lives were lost in retributive genocide.

Those who witnessed the heinous acts and those who lost their loved ones must have been haunted by their memories for the rest of their lives. Some families in Lucknow also lost their loved ones who lived in other parts of the country but they themselves escaped witnessing the graphic scenes of horror as no communal riots erupted in peace-loving Lucknow. There was no television either at that time. So Lucknowites learned from the radio and the newspapers only, what happened in other parts of the country.

Related to the partition, I have vague memories of a great uncle and an uncle, both, Freedom Fighters and fiercely against the Partition who were jailed a number of times. We children could not understand why good people were punished. Our question remains unanswered.

My clearer memories of the Partition start from the time the Pakistani refugees started coming to Lucknow. The government had to provide quick and temporary housing to them. Some kinds of living quarters were built wherever some place could be found in already crowded city. Near our house, on Balda Road, there was an abandoned veterinary hospital for horses. It was converted into living space. Each family was allotted one quarter only, which was not big enough to accommodate if there were several members in the family. During the day, weather allowing, they used to sit on Bamboo cots outside their quarters by the roadside. At night in rainy and cooler weather, they must have managed indoors like sardines. We passed through that settlement almost every day as a close relative and some friends lived past that area.

All the refugees in this settlement were Punjabis, mostly Hindus and some Sikhs. Most Lucknowites had never before seen a Sikh in person and Punjabi language was also new for them. We Lucknowites are known for our linguistic chauvinism; even Urdu from other parts of India is not acceptable to us. It took some time before Lucknowi ears got accustomed to the sound of Punjabi language. The attitudes also changed gradually and the young people started finding Punjabi a warm and friendly language and assimilated some of its expressions in their own speech: “Kee haal hai?”, “Changa” etc.

When passing through this settlement, my mother who was a very compassionate person, always sadly remarked: “We don’t know what and whom they have left behind and what they have been through to reach here.” She wanted to talk to them and make friends with them but language was a barrier. She always heard them speak only Punjabi among themselves. One day, a Punjabi lady who must have noticed mother’s keenness to talk to them, approached her and said, “Bahen Ji aao baitho gallaa’n karo”. Mother was absolutely delighted to hear some Urdu from her. She did not fully understand “Gallaa’n” but guessed. She happily sat with her on the bamboo cot and they started talking. It turned out that several other women also spoke some Urdu and gathered around her. Thus, they became friends and mother learned their individual stories of tragedies and hardships with tears in her eyes.

Then, one by one, they were moved to better accommodation.

Apart from housing, a number of schemes such as the provision of education, employment opportunities and easy loans to start small businesses were also provided to them.

In the heart of the city, in Aminabad, a market with wooden shops was set up which came to be known as Refugee Market. It’s name was later changed to Mohan Market. The shops were allotted to small businessmen who mostly sold fabric.

There were some tailoring shops as well.

I have a fond memory of an Eid after a year or two of the Partition when the refugees were still pouring in. One day during the Ramzan, our mother, my older sister Sofia and I went out shopping to buy fabric for new clothes for Eid. On our way to Aminabad, which was our usual place for shopping, entering Nazirabad near Qaisarbagh intersection, we spotted a young Sardar sitting on the pavement with some fabric rolls on a gunny sack. He had no customers and looked very troubled. We all felt very sorry for him.

Mother suggested, “Why don’t we buy fabric from him? He has no other customers.” At first Sofia and I protested saying his fabrics looked such poor quality and not at all pretty but then our mother put us to shame for our vanity, saying, “Couldn’t we wear ordinary clothes one Eid and help a poor refugee earn his Rozi (daily bread)?” She repeated her usual regrets for the displaced people now living in misery in our town. We saw her point at last and agreed to buy from him. We stopped at Sardarjee’s and asked him to give us Chhalteen- white thick cotton for men’s Aligarhi pajamas and girl’s shalwars and shirt material for the whole family. Altogether, a lot of material had to be measured. We felt Sardarjee alone could not manage it. Besides, the way he was holding the measuring stick it was obvious he had never measured even an inch of material before so all three of us started helping him. Our mother got tired soon and gave up. I also slowed down as I was a lanky and pale looking youngster (besides being lazy) but Sofia was stronger and had a lot of perseverance as well. She kept at it with Sardarjee and finished measuring all the required lengths.

Sardarjee started addressing our mother as “Ammi” so he became our “Bhai”. But we had a number of Bhais and Bhayyas in Lucknow such as our neighbour’s sons: Tahir Bhai and Waseem Bhai, Arun Bhaiya and Ajay Bhaiya etc. So he became our “Sardar Bhai” but somehow, we ended up calling him “Sardarji Bhai Saheb”; may be because he looked much older than us. His name was Sardar Harmandar Singh. I love this aspect of our Indian culture where beautiful relationships are formed instantly.

After a couple of months, our mother and Sofia went shopping again to Aminabad. But Sardarjee Bhai Saheb was not there at the footpath. They looked for him in the newly built Refugee Market and found him in his own shop. He seemed to be doing good business. He greeted them warmly and offered them hospitality by ordering tea for them. He also measured a beautiful shalwar-suit length for Sofia (he measured without her help!) saying that her helping hands proved auspicious, because soon he acquired a shop and has been doing well.

One day, some ladies from Rudauli came to Lucknow to do shopping at the Refugee Market. They happened to stop at Sardarjee Bhai Saheb’s shop as well. After talking to them for a while, he asked them if they belonged to Rudauli Shareef. The ladies were taken aback and asked how he recognized it and he said that their speech and mannerisms were very much like his Ammi’s. The ladies looked hard at his bearded-turbaned face and asked for some of her family names. When he mentioned some, they said “Acchhaa to hamari Mohammadi Khala aapki Ammi hain!” After this encounter, he gained more customers from Rudauli as now he had found more relatives there! His shop became bigger and bigger as his customers multiplied.

In a surprisingly short time, he built a comfortable house for his family and then he invited us for a meal, tempting us by saying that his wife Davinder Kaur “Khana bahot swaad banati hai” and he was right. She was an excellent cook indeed.

The Sikhs are admirable for their hard work, perseverance and belief in the dignity of labour. Nobody has ever seen a Sikh beggar.

To give the finishing touch to my personal memories related to the Partition, I must mention some events in our school. We sisters initially attended Karamat Hussein Muslim Girls’ College in Lucknow. After the Partition, when Muslim families started migrating to Pakistan, the number of girls in the classes started decreasing. Some classes were left with very few girls only. It was after a year or two of the Partition when at the end of the academic year, we brought our result cards home to show to our parents. One sister, for the first time, declared that she had the second position in her class. She always earned the first position in all the activities at home but never had a good position in school. Our father, a lawyer, who was used to probing into the matters, asked her how many girls were left in her class and she shyly whispered: “TWOî! With this amusing note, I finish talking about my personal memories of events connected with the Partition and have a look at some others’ experiences and points of view.

The Partition inspired many artists, writers, poets and filmmakers to express their lament on the cost of freedom in terms of human lives.

There have been many artistic depictions of the tragedy of the Partition but an Indian and a Pakistani artist are more famous for their works on the theme.

Ms. Nalini Malani is a leading contemporary artist who has been focusing on bold universal themes such as war, religious conflicts, oppression of women and environmental destruction. She took long to tackle a very personal theme of India’s Partition to paint. But since 1990s she has been focusing well on the subject.

The Pakistani artist Jimmy Engineer well known for his sprawling canvasses became particularly known for his Series on India’s Partition.

Turning to literature, among the Urdu poems on the theme of the Partition, some famous ones are:

Subh-e-Aazadi by Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Inquilaab by Asrarul Haq Majaz, Matam-e-Aazadi by Josh Malihabadi, Pandarah Agast by Akhtarul Iman, Aazadi-e-Vatan by Makhdoom Muhiuddin.

Some notable poems in English are:

Partition- by W.H. Auden, Go Where You Will by Jibananda Das from his Ten Poems on Partition, Poems about the Partition of India by Arpit Kaushik.

The most important prose writings on Partition are as follows:

Pinjar – by Amrita Pritam, Train to Pakistan – by Khushwant Singh, Midnight’s Children – by Salman Rushdie, The Great Partition of India – by Yasmin Khan, Freedom at Midnight – by Larry Collins & Dominique Lapierre, Ice- Candy Man – by Bapsi Sidhwa, The Other side of Silence: Voices from the Partition of India – by Urvashi Butalia, A Bend in the Ganges – by Manohar Malgaonkar, Shadow Lines- by Amitav Ghosh, Toba Tek Singh – by Sadat Hassan Manto from his collection of stories.

Among the notable films concerning the Partition, the earlier ones are:

Chinnamul-1950 and Dharamputra – 1961- by Nemal Ghosh, Meghe Dhaka Tara – 1960, Komal Gandhary- 1961 and Subernarekha- 1962 by Ritwik Ghataks.

Two later films became very popular:

Garam Hawa – 1973 , Tamas- 1987

Films in late 1900s and onwards:

Gandhi- 1981, Sardar- 1993 , 1947, Earth- 1998, Train to Pakistan- 1998, Jinnah- 1998, Madrasapattinum- 2010

The list of writings and the films touching the theme of the Partition is long and may continue to get longer always making us lament:

“Nasheiman phoonkney waley hamari zindagi yeh hai

Kabhi roye kabhi sajdey kiye khaak-e-nasheiman per.”

Dr. Sehba Ali

Writer is an Applied Linguist and a freelance-writer.

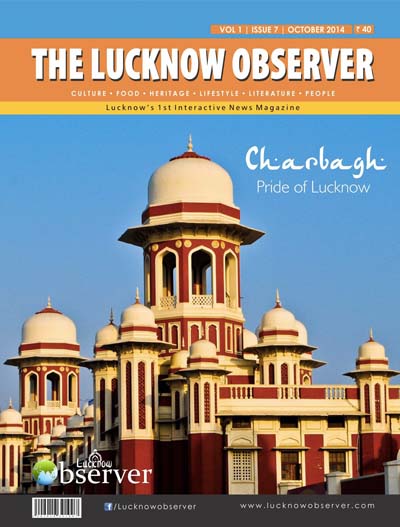

(Published in The Lucknow Observer, Volume 2 Issue 17, Dated 05 August 2015)