Jewels from Lucknow and Pakistan

How the Jewellery shines in the memories of a woman

The first and fondest memories I have of myself are the memories of my Bismillah, in Karachi Pakistan. This was November 1956, I was four and a half years old and was ready to read, hence a grand ceremony was arranged by my parents to read the first words of the Quran, the occasion was sanctified by the Bismillah ceremony. Traditionally, little girls are dressed like brides, complete with duputta (stole), jewelry, flower garlands and henna on palms. Prompted by maulvi sahab (the priest), the child repeats Bismillah and then writes it on a writing board. The inevitable feasting, presents for the child and distribution of sweets follows. I still remember the clothes and jewelry specially the ornament I wore on my forehead, the teeka, these are all safely stored in the subconscious, for instant replay.

I remember me and my sister had a fascination for jewelry from a very young age, we would spend hours rummaging through our mother’s jewelry boxes, they had some of her friend’s treasured ornaments too, they trusted her and would leave their ornaments in exchange for cash, taking the ornaments back whenever they were ready with cash, such was their pride. We were intrigued by the contents and their history, the richness of gold, the intricate patterns, shape and color.

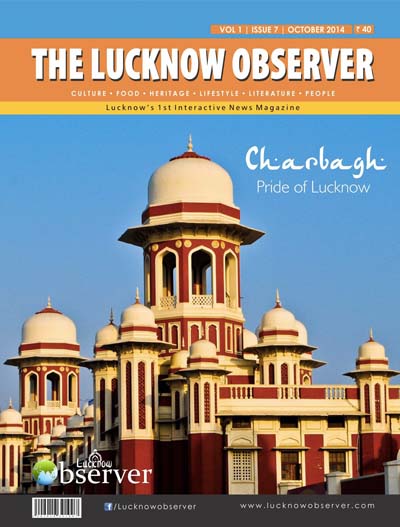

Pakistan was a new country then, my parents were young immigrants from Lucknow, India. Lucknow was the capital of Awadh (present-day Indian state of Uttar Pradesh) in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Lucknow emerged as a centre of art and culture and became famous for its architecture, poetry, music, dance and cuisine. The rulers of Lucknow (nawabs) were popular for their wealth and generosity. The culture of Lucknow was not just limited to the elite, even courtesans could quote great Persian poets, even the tonga drivers and the tradesmen in the bazaars spoke modest Urdu and were famous across India for their exquisite manners. Lucknow represented a culture that combined emotional warmth, elegance, a high degree of sophistication, courtesy, and a love for gracious living.

In 1947 the Indian sub-continent got independence from the British Empire, the colony emerged as the free states of India and Pakistan. It was a cause for celebration, but the politics and division of the sub- continent resulted in one of the largest mass migrations of individuals in the 20th century and also in the deaths and assaults of millions of migrants. Accomplished Muslims from Lucknow had emigrated en masse to Pakistan.

My parents came to Pakistan in 1951, I was born a year later. They came with just a few belongings, bidding goodbye to their families, their childhood homes, their alma- mater and the entire culture in which they grew up. However a part of them stayed behind in their beloved Lucknow, the other part evolved as sensitive spouses and responsible parents in Karachi, Pakistan. Abbu, my father would miss his siblings and his mother and would narrate to me and my sisters all the minutest details of his family and their dynamics, giving him the opportunity to relive his most cherished moments.

Clad in a crisp cotton or a chiffon saree, hair tied in a neat bun, matching glass bangles and a pair of gold karas adorned her wrists, a diamond ring in her finger and a cluster of diamonds in her ears. This was Ammi- my mother; an epitome of the rich culture she belonged to. Not only her appearance, but also her etiquettes and language aptly complimented her Lucknow roots that were so close to her heart. Ammi was a keeper of culture and a great planner. Women have historically been keepers of culture. They bear tradition on their shoulders, including the reproducing of the particular culture’s textile designs, jewelry, cultural cuisine, language, habits and morals. My mother took great pride in what she was and where she came from. Lucknow was her heart and soul. She always enjoyed the company of people from her own roots and found immense pleasure in talking about the uniqueness of her culture.

Years later as me and my sister started college, Ammi got started on her mission (my younger sister was very young at that time). The first thing on her list to do things was to make jewelry for her daughters. Gold jewelry was particularly esteemed for marriage in the Indian sub-continent. When Ammi migrated she carried some of her jewelry with her but she thought it was not enough to be equally distributed amongst her three daughters. Ammi did not want to buy the ready to wear stuff from the jewelry bazar, rather she had planned something unique, she wanted to recreate the images that were still fresh in her mind. It would not have surprised anyone if memories faded; rather distance sharpened the already etched memories and she silently but pain stalking took it upon herself to keep the torch of love for her culture burning by sticking to her traditions, and most importantly embarking on a very difficult mission of reproducing the remarkable ornaments that were in the possession of her grand mother, mother, her aunts, and other female relatives. The unmatched craftsmanship was hard to find in her new homeland but that did not deter her from her mission of getting the originals recreated.

She was determined to reproduce, she drew inspiration from her cultural tradition using imagery and incorporating ideas from what was available with the local jewelers. That was a cumbersome and financially demanding task which would not have been possible without Abbu’s financial and moral support, needless to say Abbu complied with full submission, and Ammi embarked on the passionate mission of following her heart and believing in her dreams and thus created dazzling gold studded precious ornaments for her beloved daughters. Each and every piece big or small, that she reproduced was a statement in its own entity. Ammi was preserving the cultural heritage through jewelry. The purpose of reproducing was to cherish the memory of her ancestors and their culture and to remind their succeeding generations of their glorious past.

As the process of jewelry making started, I recall how Ammi had a story to narrate…stories about how her aunt had a particular earring which was passed on to her by her mother-in-law, stories about her mother Amma giving away most of her jewelry as wedding presents to her sister-in- laws and other close relatives, that her grand mother Appun nani had a huge heavy copper box to store jewelry and how a jujnu or a balipatta was gifted to a dear one as a token of love or the narration about a theft in the family house when most of the female members of the family lost their jewelry, months later a pair of karanphool (earring) purchased by my grandfather Abba for my aunt’s wedding happened to be one of the stolen jewelry of Ammi’s cousin. Mumu jan, Ammi’s younger brother would refer to Appun nani as queen Victoria because of the jewelry she adorned that defined her personality.

Often in the stories, the everyday life wearing of jewelry and wearing them on special occasions was described. These special occasions were discussed more thoroughly when there were more emotions involved. Ammi’s maternal uncle was married to a beautiful girl from a respectable family, her parents married her in silver jewelry but when she came to her in-laws house Appun nani replaced all the silver ornaments with gold ornaments, she also gave her daughter-in-law her jhoomar (ornament worn on the head) which Appun nani adorned each day for over a year as a young bride herself.

Some pieces of jewelry are worn only on family related special occasions; Sometimes jewelry ought to be worn only on particular occasions, which has led to the situation that they have been worn only once per person. Like the jhoomar it is only worn by the brides of the family on their weddings or the weddings of very close relatives.

Similarly a kundan Teeka (worn on the forehead) by Amma was passed on to her daughter my khalajan on her wedding, khalajan gave it as muh dekhai (A tradition when the girl is seen for the first time as a bride, close relatives usually present jewelry or cash) to her brothers wife who was her cousin too, and she passed it on to her daughter-in-law. In the past, sons were married in the family, hence daughter-in- laws valued family ornaments. The above mentioned Teeka, a crescent and a star, is sadly lost…it was worn by almost every bride of the family. I wore the same teeka for my Bismillah when I was four and half years old.

The stories would go on and on. These voices echoed, they echoed around pieces of jewelry- the objects of art, these voices reflect memory, they tell a story, they signify family connections. They opened up a deeper complex meaning of immigration as subjectively experienced by my mother. It opened the individual immigrant woman, her memories, struggles, conflicts and her triumphs.

Ammi was a visionary, she could look ahead – she used jewelry to document the past because eventually human memories fade. This is especially true when people live at a distance from familiar objects and sights that continue to stimulate those personal memories, thus reproduction for the sake of documentation was an important task for preserving cultural heritage. It was Ammi’s way of expressing the inexpressible, a metaphor for memory about stories. It was her desire that these ornaments may pass on as heirlooms- a desire to stay connected to the past and create a link to the future.

The jewelry that Ammi reproduced for us was her need, her need to be connected to her roots and her need to keep the tradition of giving jewelry to her daughters. Just as a person without memory is functionally impaired, so too is a family without a link to the past. Our family history is important to us. Family memories to a larger degree lie in records and original letters, papers, documents, photographs, recorded narratives and in the Indian sub- continent jewelry. All easy to carry with you if you decide to migrate, and human beings have moved from place to place since time immemorial. I recently moved to the North America.

Being an immigrant myself made me better understand my parents deep affection and loyalty to their culture. I can now discern Ammi’s emotional turmoil of migration…I know how I want to hold on to my culture. But I migrated at an age when my responsibilities are over, I neither have the need nor the desire to make new ornaments. But I was curious to find out what images my mother had in mind when she was designing the guluband, the jhumka, balipatta, the teen lara, the dastband etc. I decided to do some research.

As I started informally interviewing my family and my people for collecting photographs of family ornaments, I noticed that fewer and fewer people are now left with classic pieces, I am now very apprehensive that jewelry of my ancestors will be lost and will be unheard off to the future generations. My family narratives made me understand why more and more people were no more interested or attached to family ornaments. Some mentioned economic reasons: “gold has become extremely expensive”. They sold their ornaments for children’s education or whatever the need was. For some priorities had changed, they prefer fancy cars and Apple products. There were others who thought it was not safe to wear gold, its just lying in the bank and you pay zakat on it. Some relatives were of the opinion that daughter-in-laws are now not from within the family, rather they come from outside the family, they are from different regions at times from different countries, and prefer modern jewelry. Some mentioned that their girls now want to identify themselves with movie stars and models to look modern. Some relatives narrated: our young girls are now wearing hijab, thus foregoing the necessity to wear any ornaments. Many of my extended family members have migrated to western countries, and their narrative was, “we want to assimilate into the new culture, moreover artificial jewelry is so much better and easy to maintain”.

These narratives were heart breaking, especially the one that made me cry, when I heard that my great grand mother’s jhoomar had been sold, (this happened very recently) it was a beautiful kundan ornament with two peacocks one on each side and intricate meena kari work on the back. Appun nani’s jhoomar was the adornment of the family’s brides. This more than a century old jhoomar was brought in to the family wedding occasions to adorn the brides, and had been worn by numerous brides of my family. Thus many of Appun nani’s and Amma’s finest pieces of jewelry were given away as wedding presents to their relatives, some were stolen, others sold and cannibalized. Changing economic conditions, migration and relocation there after played a major role in the loss of some great family ornaments.

I took upon myself this daunting task, of collecting pictures of family ornaments for the purpose of documentation. It was difficult to persuade people to share pictures of ornaments that belonged to their ancestors. It was challenging because now its been five generations and the family tree has branched out, spread over continents, there were some third cousins whom I spoke for the first time. But I was hundred percent successful in getting photographs of my ancestors ornaments that are still in family possession. I was spellbound, amazed at my mother’s photographic memory and charmed by her ability to reproduce from imagery.

These photographs are my way of peeking into my mother’s memory. I have a personal relation with these objects of art, and what impresses me is the way they reveal a story, the memories and voices that echo with these objects. I am using photographs of ornaments as a beautiful tool to create links between generations. These photographs of family ornaments may be employed as a positive agent for understanding the challenges and opportunities of migrants. The collection can also be seen as a way to build creative links between the past, the present and the future.

This documentation of jewelry is for the future generations so they can stay connected with what Ammi started, I am not reproducing any jewelry but I have collected pictures of hand crafted ornaments that belonged to my great grand mother, my grand mother and my mother.

Today when I see my daughters, my daughter-in-law, my sisters, my nieces and my cousins wearing those jewelry on family occasions, it gives a feeling of being part of a kinship, its not just pleasing oneself and others by looking good. We feel that the jewelry we are wearing connects us to our family. We do communicate with our jewelry, and connect ourselves to the family history with the jewelry of our ancestors. I feel, I carefully picked some jewels from the archive of my mother’s repertoire of memory, only to forge a cultural identity for generations to come.

Sabiha Alwy

Writer is originally from Lucknow, migrated to Pakistan and now settled in US. She is an expert of Psychology